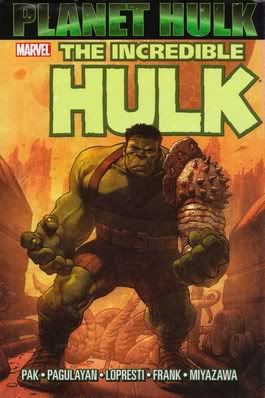

Incredible Hulk: Planet Hulk HC

Incredible Hulk: Planet Hulk HCBy Greg Pak, Carlo Pagulayan, Aaron Lopresti, et al.

Published by Marvel; $34.99

Collects Incredible Hulk #s 92-105, Giant-Size Hulk #1, Amazing Fantasy #15, and Planet Hulk Gladiator Guidebook

You probably wouldn't expect the phrase "Hulk got too smart," but it's true. It didn't happen all at once and it didn't happen without good reason. Incredible Hulk needed Peter David to get more cerebral with the mythology, to delve into the abuse-ridden childhood Bill Mantlo outlined in his penultimate issue, to be the first writer to actually diagnose Bruce Banner with Multiple Personality Disorder, and to give us more than a half-dozen different versions of the green-sometimes-gray goliath because it brought some much needed depth and complexity to the franchise. The story of a man trapped in an endless Jekyll/Hyde cycle because of an atomic blast made way for the story of a man whose tortured past made him a monster, and the more mature definition was a success. David experimented with Bruce Banner's fractured psyche, making whole new character's from the scientist's trauma. He was a gray thug, a Las Vegas leg-breaker, a cunning rocket scientist who could shoulder mountains, and at one point Banner even switched places with his alter ego; with Banner controlling the body of the Hulk and, if angered enough, changing to the weaker body of Bruce Banner controlled by the Hulk's childlike, brutish mind.

Eventually, it got to be too much. Writers simply wouldn't approach the character unless they had a radically different, intellectually convoluted interpretation of the Hulk and his history. Somewhere between Paul Jenkins portraying a literal army of alternate Hulk personalities lying dormant in Bruce Banner's mind (including a Clown Hulk and a Lizard Hulk and a Salesman Hulk) and Bruce Jones writing scenes with dueling secret agents quoting Shakespeare and Coleridge for no reason, the "smart" of Incredible Hulk got pretty stupid.

Thankfully, someone shot Hulk into space where he could beat up a bunch of aliens.

With Civil War on the horizon, 4 members of the Illuminati - Iron Man, Black Bolt, Doctor Strange, and Mister Fantastic - conspire to rid the Marvel superhero world of its most troubling citizen. They trick Hulk onto a space shuttle but, instead of returning him to Earth as promised, they blast him deeper into the void. A recorded message apologizes, explains, and promises the Hulk he will soon land on a new world where there's no one to hurt the Hulk, or to be hurt by him. Instead the shuttles crashes on Sakaar, a world of Roman-inspired tyranny where the Hulk is pressed into service as a gladiator. He earns the title The Green Scar and leads his Warbound: a patched together band of natives and displaced aliens. Having cut the despotic Red King in his first arena bout, the Hulk's continued existence and the rebellion he inspires threatens the King. Eventually the Hulk, reluctant at first to aid the insurrection his example has roused, leads a worldwide revolt against the psychotic Red King.

He fights robots, bug people, lava monsters and a hot alien ninja chick; and Coleridge's poetry doesn't come anywhere near it. Writer Greg Pak lets his readers know his intentions right away. At the end of the first issue Hulk and the insectoid alien Miek - who would become the Hulk's sidekick, ally, and eventually his enemy - are transported to the deadly gladiatorial school The Maw. As Miek cries out in fear, the Hulk says, "What are you crying about? This is gonna be fun." The dialogue is Pak's mission statement. It's a promise and he keeps it.

Pak's vision for Planet Hulk was the journey of an epic hero. The memorable open narration reads like the opening of an epic poem chronicling the adventures of a Heracles or a Beowulf: "This is the story of the Green Scar. The Eye of Anger, the World Breaker...Harkanon, Haarg, Holku...Hulk. And how he finally came home." As he survives certain death again and again in the arena - as more of the Red King's oppressed citizens discover the Hulk's spilled blood revives long dead plants from the dry soil - the belief spreads that the Hulk is the Sakaarson: an ancient figure of Sakaarian prophecy who is said to either save the world or destroy it.

Planet Hulk is strongly inspired by older Hulk stories and Pak is not shy about admitting it. The extreme nature of the Hulk's exile, and the fact that Doctor Strange is involved with it, is reminiscent of Bill Mantlo's Crossroads Saga (a story Pak paid tribute to again in Hulk Vs. Hercules: When Titans Collide). With the star-crossed love story between Hulk and Caeira as well as Hulk's immersion in an alien society that is technologically more advanced than our own, yet culturally much like civilizations of our distant past, it is difficult to not be reminded of the classic stories of Jarella's world. Pak references the similarities himself in the chapter reprinted from Giant-Size Hulk #1. Bruce Banner catches the Hulk dreaming of Jarella and her microscopic world. He scolds the Hulk with, "Look at you. Living these old stories again. Ugh. This is embarrassing." The short story is filled with similar references to other books, including jokes aimed at Ultimate Wolverine Vs. Hulk and the Hulk's guest appearance in Sentry.

While Planet Hulk is influenced by older stories and focuses more on action than psychological intrigue, Pak proves he can still tell a smart story that takes the character in interesting directions. The aforementioned Giant-Size Hulk #1 is a perfect example. Bruce Banner's paler self is absent for most of Planet Hulk and Giant-Size Hulk #1's "Banner War" tells us why. After the Hulk and his Warbound escape from the arena with a small army in tow, Banner tries to resurface. Pak applies an oft-used Incredible Hulk device: he gives us a battle between Hulk and Banner not in the physical world, but in their shared mind. Over the years Hulk has given us a lot of dreamy sequences in which Banner and Hulk meet to hash things out either literally in dreams or on some kind of hypnosis-induced mental plane. "Banner War" turns the paradigm on its head. Instead of Banner shown as an innocent victim of the Hulk's overpowering anger; Banner is portrayed as an emotional tyrant trying to belittle the Hulk into submission. It's Banner, and not Hulk, who viciously rips at his alter-ego's insecurities in order to prove he's the dominant persona.

Pak's Hulk resembles the so-called "Grayvage" Hulk who appeared at the end of David's tenure on the title; the more thuggish tone of the gray Hulk coupled with the emotional instability and physical power of the green Hulk. It's perhaps my favorite incarnation of the character because it preserves the Hulk's unpredictable nature and myopic rage, but without letting him sound like an imbecile.

Pak attempts to answer the question of whether or not Hulk really is a hero. That sounds fairly trite on the surface, even like something you'd expect to read in a Marvel solicit. Regardless, I'd argue it's a question that still confounds Marvel's writers. Obviously, he's a hero in the literary sense, but what about the morally narrow superhero sense? He's fought crime and supervillains. He's saved the world. But he's a wild card. He can be as much or more of a hindrance than a help, which is why the Illuminati exiles him in the first place.

On the other hand, Sakaar is a place where the Hulk can be a hero; a place without the crowded fraternity of Marvel superheroes and a place where the Hulk is still the strongest one there is, but not so much stronger that everyone around him knows only terror when he's near. I don't think Pak ended the first 4-part chapter of Planet Hulk with a Hulk/Silver Surfer battle just to have the story touch base with the rest of the Marvel proper or to fuel online Versus debates. I think when the Hulk pounded Surfer into the arena floor, it was his final rejection of Earth (obviously Surfer isn't native to Earth, but that's where Hulk knows him from). As far as Hulk was concerned, from that moment on he belonged to Sakaar.

I think it's a shame that the Hulk ever returned to Earth. I enjoyed World War Hulk. However, Sakaar offered a chance to see a new and interesting side of the character. The Hulk at the end of Planet Hulk - before the event that sends him raging back to Earth - is a guy I've never seen before. He's a selfless barbarian-king, practically Christ-like how he stands between his new subjects and that which endangers them. The scenes of Hulk as the Green King - like Hulk sitting proudly on his new throne, letting the Spikes feed greedily on him to keep them docile, or when he forces the bugs and pinkies to skewer him with spears and swords meant for each other - are some of my favorite in the character's history. I find it tough to believe there weren't interesting places Pak or other writers could have gone from there.

In fact, Planet Hulk convinces me that the Hulk belongs in space. More and more, I tend to doubt Stan Lee originally intended the Hulk to have anything to do with the world of superheroes. I think the Hulk makes more sense in the bizarre cosmic mythology of skrulls and kree and rocket raccoons than in that stranger asylum of super soldiers and Iron Men who find Hulk so unsettling they Major Tom-med his ass.

Carlo Pagulayan quickly won me over when these issues were first released. His Hulk has a more heroic air than most though without, unlike Dale Keown or Gary Frank's more conventionally superheroic Hulks, sacrificing his inherent wildness. I remember being immediately impressed with what I felt was a great understanding of the Hulk's, for lack of a better word, bigness. There's something very appealing about Pagulayan's treatment of the Hulk's girth. He tends to extend it to parts of his body, like his teeth, that other artists don't normally tend to draw as being particularly big or thick (I know I'm setting myself up for plenty of jokes), and even to things he carries; like swords. Pagulayan takes a break in the middle of the story and Aaron Lopresti takes over penciling for a bit. You certainly feel Pagulayan's absence, but Lopresti is sensitive to the unity of the overall story and there are places where you might not necessarily know there was a different artist.

The only dislike I harbor for Planet Hulk lay in what came after. It was such a clear success that the Hulk's trajectory in the Marvel Universe suddenly became more of a priority, spawning his own event crossovers and of course Jeph Loeb's Red Hulk.

But that doesn't color my appreciation of Planet Hulk. It was a great, epic adventure story brought to Hulk fans after years of stunningly mediocre, pseudo-intellectual nonsense. Marvel gave Pak much more time to tell his story than was customary and managed to maintain more visual unity over the course of 14 issues than you generally saw within 3 or 4. It wasn't the most innovative story in the world but it was a smart, fun space war and it's one of the few collections of which I insisted on buying the hardcover version. It deserves its spot among the classic Hulk stories and I'd argue there isn't a Marvel reader out there, Hulk fan or not, who shouldn't consider it required reading (well, maybe Silver Surfer fans).

Mustaine: A Heavy Metal Memoir

Mustaine: A Heavy Metal Memoir

Samurai: Heaven & Earth Vol. 1

Samurai: Heaven & Earth Vol. 1

There seems to be an -- understandable, if not necessarily accurate -- impression in the House of Ideas that you just cannot write a compelling story about a big green guy who breaks stuff. But, he's one of their household names, so canceling the title isn't an option. The result is that any writer hoping to scribe the character needs a very specific gimmick. They need to re-write his origin. They need to change his speech pattern and his skin color. They need to make him eat nurses and slaughter half of Manhattan. They need to drag him through a four-years-long conspiracy thriller that reads like old people sex.

There seems to be an -- understandable, if not necessarily accurate -- impression in the House of Ideas that you just cannot write a compelling story about a big green guy who breaks stuff. But, he's one of their household names, so canceling the title isn't an option. The result is that any writer hoping to scribe the character needs a very specific gimmick. They need to re-write his origin. They need to change his speech pattern and his skin color. They need to make him eat nurses and slaughter half of Manhattan. They need to drag him through a four-years-long conspiracy thriller that reads like old people sex.