Before the week that followed 9/11 was over, I started hurting myself in my sleep. The first time, I sat up in my sleep and threw myself backwards against the wall; I awoke just in time to feel my head crash against it. For a little over a month, it continued. Sometimes, while asleep, I stood up, grabbed something like a small bookshelf or my desk chair and threw it at the floor. Sometimes I threw myself at the floor. Once, the metal edge of my bed frame caught me inches away from my eye. Once, I fell asleep in my bed and woke up sitting on the toilet. Perhaps the strangest incident happened after the nightly violence turned into sleepwalking. As I sleepwalked, I dreamed of myself teaching a class about my sleepwalking. The dream ended with me tapping a wooden pointer against a blackboard and saying, "And this is the part where Mick falls on the floor and hurts his knee." I awoke, already falling, and landed on my knee. One of the last incidents ended with me waking to find my hand hovering over the knob of my apartment's front door.

When I finally saw a doctor, I was diagnosed with Sleep Apnea, but that alone didn't explain why I was sleepwalking or beating the nocturnal crap out of myself. Apnea occurs when your throat closes during sleep. Your body wakes you up so you don't choke, but it's so brief you don't remember. It causes sleep deprivation because the apnea prevents you from reaching the kind of real, deep sleep in which you actually get rest. But it doesn't generally cause people to go on sleepwalking rampages. My doctor suggested that the best explanation was that the apnea opened the door for trauma to manifest itself during sleep, but it didn't cause the trauma. That was the best explanation I ever got.

I am painfully aware how this might read. As I debated whether or not to include this story in this piece, all I could think of was BJ Novak's character on The Office telling his on-again/off-again girlfriend that he'd treated her so poorly because, in part, he hadn't "really processed 9/11." Unlike far too many people, I can't unfold any tragic stories that would explain it. I lost no friends or family on 9/11 and I wasn't in New York City. Regardless, when I tell you the Me that existed on September 10th was a different animal than the Me that woke up on September 12th, I expect most of you may know what I'm talking about.

September 11th made me afraid. I didn't fear terrorism, or at least I didn't fear it any more than I feared anything else that could kill me, nor did Arabs seem any more dangerous than every other stranger. It was simply that the reality of death finally found its way to my consciousness, and it made me simultaneously terrified and enraged. The fact that all that I am could be snuffed out without warning or mercy was a horrible crime and I had no one to complain to about it. I was afraid to fly. While I wasn't afraid to drive, I was afraid to be a passenger in a car, bus, or train. Walking outside at night became a rare event, only if necessary, and never unwarily. For the first time in my life, I considered buying a gun.

The portrayal of death in film or television was something that could ruin my entire week. Horror films became strictly forbidden, particular zombie films. I almost walked out of Shaun of the Dead. Not because it wasn't good; it was. Not because it wasn't funny; it was. Not because I wasn't enjoying myself. I was. But when they got the jerk with the glasses (you know the part I'm talking about), all my laughter ended. The movie was ruined. For a week, that grisly scene ran a loop in my mind over and over.

The worst were nature programs. I still will not watch them. In particular, I recall a show in which a pack of hyenas and a pride of lions fought over a kill. After a brief scuffle, the hyenas were chased off, but not before one of the lions snatched up a hyena pup and carried it back to its siblings. The terrified pup cried out for its wounded parents, who stumbled away, sparing a few sad glances back at their pup. The narrator commented that the lions must really have been hungry, because they would almost never resort to taking a hyena pup as food. The scene has stayed with me over the years, as happy as I would be to be rid of it, maybe because it's the best analogy for the specific fear 9/11 gave me - being made helpless, alone, ripped from the people I know and love, and everything I am and ever could be smothered under the hungry breath of strange, alien bastards.

Alan Moore and David Lloyd's V for Vendetta was one of many comics which, until very recently (as in the last few weeks) was on my "must read, what the hell are you waiting for" list. So when V for Vendetta was released in theaters, I had little idea what it was about. In fact, not only did I not feel an overwhelming urge to see it, but for a while I was very much against seeing it precisely because I wanted to read the comic first. When my girlfriend of the time finally pressured me into going, I certainly had no clue that it would reduce me to tears.

It was a clarion call. It was an anthem. It wasn't the first. Despite Bush's re-election (or simply election, depending on who you talk to), it isn't like the Wachowski Brothers were the first people to make powerful creative statements about the administration's fear-mongering. By 2005, Jon Stewart alone had bloodied his knuckles over and over on Bush's jaw and, like Iraq and Afghanistan, no end was in sight. But V for Vendetta was different. V was miraculously defiant in its treatment of 9/11. It took our real history and turned it on its head. It took the event that was such a horrific, deadly defeat - the terrorist destruction of iconic buildings - and made it the film's conclusive victory (of course, V's destruction of Parliament is spared the loss of lives, other than his own). The fact that the story's setting is England likely helped it enjoy success in the United States. If it were set in America, I don't know that thoughts like "...the world needs more than just a building right now," or "...with enough people behind it, blowing up a building can change the world," would've been tolerated from the same population that would later suspect our current President of terrorist subversion because his last name had more vowels than consonants.

The reason why V for Vendetta had such a profound impact on me had less to do with its indictment of contemporary politics, however. Its true enemy was fear; the kind of fear that immobilizes us all - at one time or another if not perpetually - and stops us from living the lives we want and desperately need to live. Perhaps the most powerful moment in the film for me was Evey's imprisonment. The emotional power of that sequence springs mainly from the story of Valerie - the test subject who was incarcerated for being a lesbian and wrote her story on a piece of toilet paper for Evey or any other prisoner to find. The line that still makes me cry - not purely because of sadness but a deep, almost primal defiance against the fears that 9/11 unleashed - both in the film and the comic from which it originates is Valerie's simple proclamation "...for three years I had roses, and apologized to no one."

The film struck me so deeply that I easily forgave the kinds of things that would make me groan in any other film. V's miraculous survival after being riddled with bullets, the unmasking at the end revealing dead characters, and Evey's I'm-V-You're-V-He's-V-She's-V-Wouldn't-You-Like-to-be-V-too speech would, in any other film, stink far too much of a Hollywood pseudo-statement to have any impact on me, but in this case it was the perfect ending to a film that made me feel like I had been waiting for nothing but that film for 4 years.

Afterward, I assumed the film followed the comic relatively closely. I didn't read it. Didn't check. But I assumed it to such a degree that I believe in conversations I actually told people, "Yes, they're fairly similar." I wasn't lying. I mean, I guess somehow I was lying, but not consciously. The film had been so important to me, that I couldn't imagine the filmmakers had strayed far from the spirit of the comic. Not to mention that in spite of the widely publicized conflict between Moore and the filmmakers before V's release, it proved to be not only the best adaptation of a Moore comic I've seen, it remains the only one that wasn't so frustratingly stupid it made me want to punch a baby (though I have yet to see From Hell, so have no opinion on that either way).

When I decided to write this article, it was obvious that it was finally time to read the comic. As I read and noticed the many differences between the comic and the film, it was almost shocking to see just how much had been changed. I don't mean the cold, hard facts of the plot or the timeline. Sure, different stuff blew up and blew up at different times. Prothero was a radio propagandist rather than a TV propagandist, and he was driven insane rather than being murdered in his shower. The film didn't mention the supercomputer Fate. The Creedy of the comic didn't even show up until towards the end. Tons of important characters in the comic were jettisoned, there was no mention of bio-terrorism, and Finch dropped acid. But none of that stuff mattered to me. In discussions of adaptations, I've always said that if the spirit of the story remains the same, then, within reason, everything else is negotiable.

My appreciation of both the film and the comic challenges that notion, however, because it's now clear to me that the "spirit" of the two stories are very different. There are similarities, obviously, and more than just cosmetic ones. The story was retooled for a post-9/11 world, and the power of the original story is blunted.

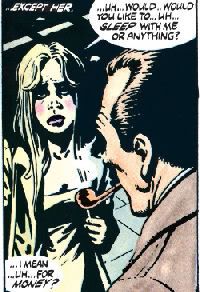

The first thing that surprised me was Evey. Evey is a hooker in the comic, not a secretary like Natalie Portman's version. More importantly, Portman's Evey is fairly educated by the time she encounters V, whereas the comic version is rather ignorant until the later chapters of the series. My initial assumption was that the filmmakers worried Evey wouldn't be sympathetic to audiences if she were a prostitute. During a Making Of special on the V For Vendetta DVD, director James McTeigue claims the changes were to make the character stronger and more independent. One could argue that misses the point; that Moore purposely wrote Evey uneducated as an indictment against a government that was willfully trying to produce less educated, and hence more easily controllable, citizens. In the comic, Evey is the best candidate for a reflection of ourselves. While we can bicker about whether or not some of us live in an "actual" democracy, I would think we can all agree that neither the UK nor the US suffers under the kind of blatant police state that's depicted in V for Vendetta. For a time, neither does Evey. Once V shelters her in the shadow gallery, she is safe from the oppression and even from the responsibility of supporting herself. We see her lounging comfortably watching old movies, and by the nearby scattered tapes on the floor, it seems clear that this is just about all she does. The world needs change and in response she drowns herself in mindless entertainment. Sounds kind of familiar.

The first thing that surprised me was Evey. Evey is a hooker in the comic, not a secretary like Natalie Portman's version. More importantly, Portman's Evey is fairly educated by the time she encounters V, whereas the comic version is rather ignorant until the later chapters of the series. My initial assumption was that the filmmakers worried Evey wouldn't be sympathetic to audiences if she were a prostitute. During a Making Of special on the V For Vendetta DVD, director James McTeigue claims the changes were to make the character stronger and more independent. One could argue that misses the point; that Moore purposely wrote Evey uneducated as an indictment against a government that was willfully trying to produce less educated, and hence more easily controllable, citizens. In the comic, Evey is the best candidate for a reflection of ourselves. While we can bicker about whether or not some of us live in an "actual" democracy, I would think we can all agree that neither the UK nor the US suffers under the kind of blatant police state that's depicted in V for Vendetta. For a time, neither does Evey. Once V shelters her in the shadow gallery, she is safe from the oppression and even from the responsibility of supporting herself. We see her lounging comfortably watching old movies, and by the nearby scattered tapes on the floor, it seems clear that this is just about all she does. The world needs change and in response she drowns herself in mindless entertainment. Sounds kind of familiar. Of course, there's V himself. After reading the comic, it's difficult to deny just how watered down Hugo Weaving's V is. The filmmakers claimed they wanted to make a morally ambiguous character but, at the end of the day, there's very little that feels ambiguous about him. If we coldly examine every single action he makes, sure. But he feels like a good guy, and it feels like we're supposed to think that's what he is. I don't think as an audience we ever have much doubt about it. Sure. He kills people. He isn't Spider-Man. But one of the most popular comic book (and now movie) heroes of the day fights evil by punching steel claws through people's skin. In Bay's second Transformers adaptation, Optimus Prime, the hero of a kids cartoon, blasts off helpless decepticons' heads after saying, Dirty Harry style, "Any last words?" And when we watch Uma Thurman in Kill Bill wade through dozens of men who will soon be nothing but chopped up meat and bone, we laugh. And we're meant to. Compared to just about every other action hero out there, Hugo Weaving's V might as well be Gandhi. In fact, while the film's V vengefully pursues the half-dozen or so bigwigs from the concentration camp where he was experimented upon, in the comic it's suggested he eventually killed every single employee of the camp - over fifty people.

Of course, there's V himself. After reading the comic, it's difficult to deny just how watered down Hugo Weaving's V is. The filmmakers claimed they wanted to make a morally ambiguous character but, at the end of the day, there's very little that feels ambiguous about him. If we coldly examine every single action he makes, sure. But he feels like a good guy, and it feels like we're supposed to think that's what he is. I don't think as an audience we ever have much doubt about it. Sure. He kills people. He isn't Spider-Man. But one of the most popular comic book (and now movie) heroes of the day fights evil by punching steel claws through people's skin. In Bay's second Transformers adaptation, Optimus Prime, the hero of a kids cartoon, blasts off helpless decepticons' heads after saying, Dirty Harry style, "Any last words?" And when we watch Uma Thurman in Kill Bill wade through dozens of men who will soon be nothing but chopped up meat and bone, we laugh. And we're meant to. Compared to just about every other action hero out there, Hugo Weaving's V might as well be Gandhi. In fact, while the film's V vengefully pursues the half-dozen or so bigwigs from the concentration camp where he was experimented upon, in the comic it's suggested he eventually killed every single employee of the camp - over fifty people.The V of the comic is a different animal. When I first read the comic, it struck me how much V reminded me of the Joker. While he displayed theatrical tendencies in the film, we never see him do something along the lines of having one-way conversations with statues he's about to destroy. As I mentioned before, rather than poisoning Prothero in the shower, in the comic V doesn't even kill the propagandist. He catches up with him on a train, kills his bodyguards, and brings him to a very Joker-y funhouse presumably somewhere in his subterranean home. Earlier on, we learn Prothero is a prolific doll collector, and V destroys all of his dolls before his eyes. In a very classic Joker move - really in a classic super-villain move, not just Joker - V takes over the airwaves to address the population. While in the film, the citizens of England are given a rousing, freedom-loving speech from a mysterious hero, in the comic, V ends a satirical retelling of the history of the world by threatening that if the citizens of England don't get their crap straight, he's going to kill them all.

Throughout the film, we never really get a clear idea of what would be an ideal world to V. He wants to topple the government, but we never learn what he wants in its place. The anarchy comic book V envisions seems much more important to him than it is to the movie V. Ironically, the result is that while the comic book V is much darker, his counterpart in the film seems more driven by revenge than by political change. The comic book V very clearly wants anarchy and gives us an explanation of how he sees it. The world he wants is something I would guess most readers would question, if not outright reject. What we we get from the film is much more palatable. He tells Evey "People should not be afraid of their governments. Governments should be afraid of their people," which would seem to suggest he wants something closer to a democracy, not anarchy.

The comic actually shows at least a little bit of the aftermath of V's conflict with the government. A once powerful woman begs Finch to save her from a group of men camping outside who, she claims, she is forced to sleep with for food and shelter. This isn't the world that we imagine remains after the destruction of Parliament in the film, and the willful creation of such a world raises a lot more questions. There is, in other words, real moral ambiguity in the comic. Not so much in the film.

More than any other changes, the omission that bothered me more than just about anything else was the lack of any discussion of race in the film. It's made clear in the comic that one of the worst consequences of Adam Susan's rise to power is the wiping out of the black race. I may be wrong, but I cannot remember a single mention of this in the film. Thinking back on it, the only non-white faces I can recall seeing in the film were those of prisoners in the concentration camps, but I didn't notice at first because it isn't explicitly mentioned in the film and it isn't like a lack of non-white faces is particularly rare in major motion pictures.

Watching the Making Of feature on the V for Vendetta DVD didn't help my steadily dropping opinion of the film. I'd say the first 5 minutes or so of the feature is taken up with the various filmmakers and actors very defensively (in some cases, they really do seem a little nervous and twitchy) justifying the differences between the comic and the film. There are no explicit insults about Moore, but there's certainly a healthy amount of condescension. Perhaps what annoyed me the most was McTeigue claiming he had decided to not reveal V's face because he wanted to go against audience expectation. It just seemed to me that, with everything they had - for better or worse - changed about the story, it was a little disappointing to hear the director take credit for one of the few things he simply lifted directly from the comic.

It took me some time before I could decide upon what I would write in this column. I don't know that I've ever felt more ambivalent about a film. V for Vendetta is a blunted version of the comic. It's watered down. It does not live up to the spirit of its source material.

I don't care. I needed V for Vendetta.

Obviously, a movie alone didn't and couldn't purge me of anything. I'm still afraid. I struggle with it. I have to force myself during simple, stupid things, to let go and stop being afraid. Ask my girlfriend how long it took me to be able to be a passenger while she drove without tensing up and gasping every few minutes. I sometimes double-check, triple-check (or more), the locks on my front door. Just in the past few weeks, during the bus drive home, when it takes a particularly nasty curve of bridge over the Hudson and some silly part of my brain tells me the bus is top-heavy and it's going to topple over the guard rail and squash me into nothing, I've learned to not do it - to not tense up my legs, to not grab onto the seat in front of me for dear life while trying to not look horrified to the other passengers (who, unlike me, keep reading or lounging, as comfortable as they would be in their own living rooms). But before I learned to stop myself, before I learned to even begin facing the fear, I needed someone to tell me what's really important. What is really important is not that what I fear at any given time won't happen, because that's a lie. It might. And ultimately, in one way or another, it will. What's important is that if the worst happens, if they take me behind the chemical shed and shoot me, I need to remember what it is to always be afraid, and know there are worst things than dying behind the chemical shed.