No, the Burn has not died out. My long break from the blog was due mainly to a very stressful apartment move, computer problems, and some medical issues. I regret I wasn’t active enough to report the Comic Book Galaxy relaunch, but, well, it relaunched. You probably already know that. There’s a very goofy pic of me on the new staff page. Enjoy.

Without further a-diddly-do, I’ll celebrate my return to the blog with look at the film probably everyone else on the blogosphere has already tackled: Batman Begins.

(For the few who haven’t yet seen the film, spoilers follow, in particular a mighty big whopper of a spoiler shows up in the following paragraph)

I’m not sure if I agree with Logan Polk that Watanabe was wasted. On one hand I sympathize as I was looking forward to his performance, having only witnessed his talent in The Last Samurai (and his performance was wonderful, while the film not-so-much - it’s not bad, but if you’ve seen Dances With Wolves and Braveheart, there’s really no reason to see it).On the other, the fact that he was used as nothing more than a decoy is indicative I think of how committed the director was to the film. In other words, while it’s frustrating that an Oscar-nominated talent was recruited simply as a decoy, I love the fact that they actually hired Oscar-nominated actor just to play a DECOY! I don’t know how Nolan managed to assemble such an A-List cast, especially considering what a massive failure the last Batman film was.

When I first heard about the cast, my only concern was Cillian Murphy simply because I’d never seen him in anything, but ultimately I thought he played a wonderfully officious and chilling Scarecrow. Gary Oldman was perfect as Gordon, though like ADD I had hoped, as was the case in Batman: Year One, we’d see more of his life and more of a parallel between his situation and that of Wayne’s. Bale was gave us a much more frightening Batman than we’ve ever seen on film and utterly believable in his double role as fake airhead playboy/shrewd, cunning businessman. I was particularly hopeful for the film when I heard that the director of a Batman franchise film finally realized that a guy who leaps from rooftops and has kung-fu ballets every night should LESS THAN FUCKING FORTY YEARS OLD (after doing some quick research at IMDB: Kilmer and Clooney were both 36 when they made their respective Batman films, while Keaton was 38, and Bale is 31, apparently the Dark Knight lives backward). Unlike a lot of folks, I have no problem with Bale’s disingenuously deep Batman voice, simply because I see no difference between it and any of the silly voices past actors have given him. Perhaps my only complaint as far as the casting is concerned was Tom Wilkinson as Carmine Falcone. I’ve just seen too many movies featuring Wilkinson as a noble Englishman that I couldn’t buy his crimelord accent.

I can’t completely disagree with Peter David’s comment that “the fight sequences seemed to have been edited by putting the film into a blender, leaving the top off the blender, and starting it up,” and at first the style works. Batman should move too fast for the human eye, or the camera lens. You shouldn’t see every kick and punch. As much as I love both of Burton’s films, the Batman of Begins had something Keaton’s rendition (and certainly Kilmer’s and Clooney’s) lacked: he was SCARY, and he should be scary. And the confusion of the various melee scenes helps to show the audience exactly why criminals could be frightened of a guy in tights, and why an entire city would eventually deify him.

Unfortunately, the result is that when things finally do slow down and we’re able to get a clear view of Batman, he looks that much more ridiculous. In part, this is compounded by how far Nolan goes to inject realism into the story. The extended origin story is there to convince us that a young boy really could evolve into a guy who dresses like a bat and beats people up, and it works. He convinces us that yes, there IS a way a guy in Wayne’s situation could maintain his secret, that he could get all those nifty gadgets without sending off any alarms at the Department of Homeland Security. But he injects almost too much realism. He tries so hard to not make it comic booky, that once the more blatant comic book elements arrive, it’s that much more difficult to swallow them. Burton solved the problem by giving us the more cartoony elements up front. We met Batman before we met Bruce Wayne, and in fact he never even bothered to explain what we already knew - that they were one in the same. Getting the guy in tights up front made it that much easier to swallow the psychotic clown and the penguin man and everything else.

Overall though, I enjoyed the film. I think Nolan did a wonderful job at depicting Batman as a dark, legendary character who would live in the hearts and minds of Gotham as more Boogeyman than Superman. Among other minor things, I was happy that that Joe Chill, not the Joker, killed Wayne’s parents. Not because it makes it more comic-book-accurate, but because it decisively severs these films from the Burton/Schumacher continuity. I’m also glad that, unlike too many superhero flicks, Nolan felt no need to kill off all the villains. Even Ghul’s death was not necessarily carved in stone (if you don’t see a body...though I said the same thing about Sabretooth and Toad after X-Men). When they kill off the villains, it feels like they’re trying to claim this is the absolute, defining conflict between the characters, and besides we all know this wouldn’t have been made if there weren’t sequels in mind. Why not keep a little suspense alive with the possibility that villains could return?

Perhaps the best compliment I can give the film is what I said to my girlfriend right after leaving the theater: “God. I haven’t had to pee that bad since Return of The King.”

Tuesday, June 28, 2005

Batman Begins: My need to urinate proves its greatness

Labels:

Movies

Wednesday, June 01, 2005

Overdue Books #2

A few years ago I got sick. Real sick. Never really figured out what it was. I was dehydrated and couldn’t keep anything down. When a hospital was finally kind enough to admit me, I was diagnosed with mononucleosis. I never really believed it though. Interesting fact I never knew before then, but apparently if you’ve ever contracted mono you’ll always test positive for it and I’d had a particularly nasty case of it in the fourth grade. Anyways, that’s all they found so they ran with it.

A week or so before I was admitted, I experienced an interesting delusion. In the middle of the night, I woke up for a glass of water. I got my drink, went back to my bed, and sat for a while as I emptied the glass. Just before I was about to lay back down on the sweat-stained sheets, I had a revelation. A certain knowledge enveloped me. It washed over me. The origin of my illness became apparent and the overbearing weight on my chest lifted. My sinuses cleared. I felt better than I had in weeks. I laid down, pulled the covers over me, and sighed out loud, “Oh. Well, that’s good,” convinced that everything would be okay by morning.

The power of this “knowledge” was so strong that the next day I made the half-hour walk to work I’d neglected since the illness struck, only to leave a few hours later. It wasn’t that I woke up consciously believing in the overnight delusion, but its side-effect - my belief that my illness would soon correct itself and was not, in fact, a bad thing - stayed with me. Two blocks from work, I finally remembered what had inspired me to stupidly leave my bed when I should’ve been in a hospital.

The knowledge that had filled me, that had yielded such an astonishing (but temporary) physical improvement, was that my mysterious sickness was a necessary result of my induction into the long line of fictional Wakandan monarchs. The Panther God had chosen me as the next Black Panther, and I wasn’t actually sick. My body was simply adjusting to my new super powers. Understandably, I laid back down in the bed and said, “Oh. Well, that’s good.”

This week’s installment of Overdue Books is brought to you by the letter B. B is for the Boxer Rebellion and Bryan Miller and Bluegrass and Black Panther.

Bad Company: Goodbye, Krool World

Bad Company: Goodbye, Krool WorldScript by Peter Milligan, Art by Brett Ewins and Jim McCarthy

Published by DC/2000 AD; $17.95 US

As a sadistic alien race conquers world after world, humanity’s last hope may be Bad Company: a ragtag group of nightmarish freaks whose only answer to the invasion of the Krool is to become as merciless as their former captors. Lead by the unforgiving and Frankenstein-esque Kano, at first Bad Company’s ranks are filled with movie monster/solider amalgams. Turnover’s pretty high in Bad Company, though. But even if you don’t start out a monster, once you’ve been under Kano’s thumb for a while, you aren’t exactly human anymore either.

There’s a lot working against this collection. Bad Company was originally printed as 5-7 page installments in 2000 AD's Judge Dredd Magazine. I’ve never been a big fan of the shorter stories found in books like Marvel Comics Presents or the back of the same company's 90s annuals. Particularly these days, it’s rare enough for a creative team to tell a good story with 23 or 24 pages to work with, much less a quarter of that space. Reading Bad Company was like trying to navigate a highway with speed bumps at 50 feet intervals. As soon as I got interested in a particular chapter, it was over. And usually, the chapters would end with the usual, tired (though certainly not irrelevant) message of “being a soldier in war totally sucks.”

Another common theme (unfortunately another one that’s been exhausted, particularly in war stories) is the danger of men becoming the monsters they’ve vowed to destroy. The most interesting aspect of this is the artistic realization of the Krool. Short, fat, and fanged; with lopsided eyes and heads, the Krool can easily be seen as an amalgam of every racial, ethnic, national, or religious caricature ever rendered of the “other side” of an armed conflict. In a sense, it’s the perception Krool’s victims that render their captors so horrific, and eventually it leads to the good guys having to become more like the Krool in order to survive. It’s a nice touch to an otherwise pretty unremarkable story.

Another common theme (unfortunately another one that’s been exhausted, particularly in war stories) is the danger of men becoming the monsters they’ve vowed to destroy. The most interesting aspect of this is the artistic realization of the Krool. Short, fat, and fanged; with lopsided eyes and heads, the Krool can easily be seen as an amalgam of every racial, ethnic, national, or religious caricature ever rendered of the “other side” of an armed conflict. In a sense, it’s the perception Krool’s victims that render their captors so horrific, and eventually it leads to the good guys having to become more like the Krool in order to survive. It’s a nice touch to an otherwise pretty unremarkable story.The first half of the trade deals with Bad Company’s exploits on the planet Ararat, humanity’s last hold-out before Earth, and it’s pretty much a straight war story. In spite of the aforementioned “speed bumps,” eventually the rhythm of the storytelling evens out and it’s not a bad read. The second half of the book on the other hand, when the survivors of the previous volume search both for their former leader and a way to deal with the Krool for good, feels like it’s trying too hard to be a bit more weighty. The new recruits to Bad Company spend more time fighting each other than the Krool, and while it helps the characterization it makes the Krool seem a lot less threatening. With the exception of the final battle, the Krool hardly face the heroes at all, and when they do they’re treated as an afterthought.

Eventually, the question of whether or not to recommend this book comes down to a whole lot of if’s. If you enjoy war stories; more specifically if you like sci-fi war stories; if you’re curious about the earlier work of Peter Milligan; or if you’re a fan of Creature Commandos, Arrowsmith, or are looking forward to Marvel’s upcoming Howling Commandos just because the idea of werewolves and Frankensteins loaded up like Rambo makes you want to reach for your credit card; then Bad Company: Goodbye, Krool World might be for you. Otherwise, don’t bother.

Barefoot Gen, Vol. 1: A Cartoon Story of Hiroshima

Barefoot Gen, Vol. 1: A Cartoon Story of HiroshimaStory and art by Keiji Nakazawa

Published by New Society Publishers; $9.95 US

This is a book I dreaded reviewing. It’s one of those books the more intellectually elite and socially aware corners of comicdom will tell you is an absolute essential. If there is such a thing as a comic book canon, Barefoot Gen’s place among it is secure. R. Crumb has a blurb on the back cover of the edition I got from the library. The most recent US edition features an introduction by Art Spiegelman. It seems clear that if I were to say anything bad about this work, I’d get the same kind of looks from my fellow reviewers that my old English professor gave me when I foolishly called Hamlet a “lying weasel bastard.” Christian Slater learned the hard way that you don’t stomp through a Native American burial ground when Lou Diamond Phillips is nearby, and likewise you just don’t fuck with Barefoot Gen.

But, you know, it’s manga. And I’m me. And Rob Vollmar is probably shaking his head in absolute disgust if he’s reading this (if anyone is still reading this after that clumsy Young Guns II reference that, despite the inevitable resulting confusion, I felt was absolutely necessary in a review about a comic chronicling one of the most horrific events of the twentieth century, and hopefully I’ve cleared up some confusion with this tangent, and yes dammit that was the intent).

Initially, my prejudices were confirmed (and they are prejudices in the purest sense of the word, since I’ve read as much manga as someone who’s read, well, like, absolutely NO fucking manga). As we’re first introduced to Gen and his family, excess emotion is the order of the day. Gen and his younger brother Shinji seem to get beaten every few panels by their anti-war father whose beliefs bring shame upon his impoverished family, from the brainwashing school teacher who - probably not coincidentally - sprouts a moustache much like Hitler’s, from neighborhood bullies, passing soldiers, hell, there were probably some goats who kicked their asses somewhere in there. And each time, the drawings are disturbingly goofy, with the boys’ eyes getting screwy and unreal bumps rising on their heads. Characters sprout big, sloppy tears at the drop of a hat. They’ve got the big BIG eyes and the big BIG mouths that are always among the first things to be mentioned in any anti-manga tirade. I even remember, upon reading a scene when Gen’s older sister is strip-searched after being accused of stealing money from her school, thinking, “Man, even in a story about Hiroshima they come up with excuses to show tits.”

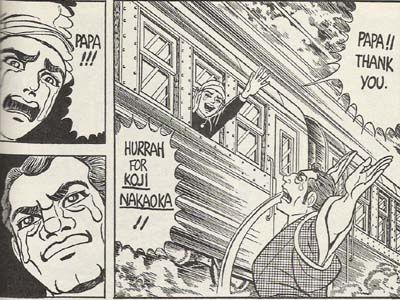

I think I am still not half the reviewer I’d like to be, because I’m not sure if I can begin to explain how or when Barefoot Gen became so important to me. Nakazawa uses no clever plot twists to pull at his reader’s heartstrings. He just tells the straightforward tale of a boy, a family, a city, and a nation before the sky fell and changed everything. All I know is that around halfway through the book, when Gen’s father surprises his oldest son Koji by calling out in pride to him as he departs for the war (a decision that sets the two at odds earlier in the story), I found myself crying big, sloppy tears. Who’d’a thunk? Consider my horizons broadened.

The only answer my limited insight can find as to how a story, that by all rights should’ve bored me to tears at best and armed me with new anti-manga ammunition at worst, affected me so deeply speaks to the question of how artists like Nakazawa and Spiegelman can so masterfully chronicle horrific events by utilizing the world of cartoon. When I first heard of Maus, for example, I didn’t really get it. Why do it? Why make the Jews mice, the Germans cats, etc.? I thought I’d finally “got it,” so to speak, when I opened the second volume to be greeted with the real life photograph of one of the victims of the first volume - a victim, until then, I’d known only as a cartoon mouse. I thought maybe the point was tell a story too horrible to be told in any way other than cartoon, and that the reader was supposed to eventually realize out loud once they’d finished the story, “Holy shit. That happened.”

Maybe that’s a part of it. I don’t know. I gave much more time to the question than I give most of my reviews, and eventually a memory of watching the cartoon film adaptation of Watership Down sprang to mind. I’ve never read the novel, so I can’t tell you much about it. I can tell you it’s a story with a bunch of talking bunnies, and these talking bunnies end up killing each other a lot. I didn’t know this, of course, when I was a little kid and came across it on the TV. I just knew it was a cartoon and there were bunnies and various state laws decreed I had to watch it. Memories of those rabbits tearing into each other, of them bleeding and twitching and dying, are still frequent cast members in my nightmares.

The point being that I came to regard Watership Down as an invasion. It was a cartoon, man. There wasn’t supposed to be blood and death. When cartoon rabbits fight, it’s supposed to be in a big, twirly cloud flanked by flashing stars. And none of them ever die. They just have halos of birds dance around their heads for a few minutes, and then they get back into it. Anvils and safes are often involved.

What Nakazawa did was to tell the story of Hiroshima in one of the most horrifying ways he could. I don’t think it was necessarily his intent. I think he was a cartoonist who used the tools he had to tell the story he wanted to tell. But I think even us seasoned comic book readers, no matter how much we despise and reject the notion that comics are “just for kids” still, subconsciously if no other way, equate comics to childhood, particularly if the style of the comic in question isn’t of the more recent hyper-real type. So Nakazawa, no matter who the reader may be, is speaking to a child, and you do not tell a child the story of Barefoot Gen. Childhood, and by extension the world of cartoon, is sacred. It’s our safe haven. You don’t tell the story of Hiroshima in the same genre that you'd tell the story of Archie and Jughead. You do not parade the melted slags of humanity the atomic bomb made out of the people of Hiroshima through the pages of a comic book. You do not stomp through a Native American burial ground when Lou Diamond Phillips is nearby with a big-ass knife, and you do not tell the story of one of history’s most merciless wartime atrocities in the panel-by-panel language of the child in all of us.

Obviously, Nakazawa does, and maybe it’s why it’s one of the most moving stories of World War II you’ll ever come across. Any debate about the right's or wrong's of the bombing of Hiroshima is always crowded with talk of American losses in the case of a land invasion, the pro's and con's of simply maintaining a naval barricade, lots of "what about Pearl Harbor" and "what about the Bataan Death March?" Nakazawa cuts through the debate and the politics and simply gives the child in all of us a picture of the hell that resulted. He invades the safe haven. The orcs have reached the Shire, and the blood’s running.

Read Barefoot Gen. It’s more important than The Omac Project. No joke.

B.P.R.D.: The Soul of Venice & Other Stories

B.P.R.D.: The Soul of Venice & Other StoriesVarious writers and artists

Published by Dark Horse; $17.95 US

The Bureau for Paranormal Research and Defense or B.P.R.D. is the group that sponsors the more well-known Hellboy. B.P.R.D. deals with the adventures of the other members of the group like the aquatic Abe Sapien and the pyro-kinetic Liz Sherman, both of whom were featured in the movie adaptation of Hellboy. Though, unlike the film, in the comics the existence of the B.P.R.D. is no more of a secret than that of the FBI or CIA. As the subtitle suggests, all of the tales in The Soul of Venice & Other Stories are self-contained (though the Johns/Kolins story “Night Train” does demand just a little bit of knowledge of the ongoing storyline), with each story written and drawn by different creators. The heroes are called into locales across the world to deal with supernatural occurrences, kind of like a paramilitary X-Files except most of the agents are just as steeped in magic as the threats they face and the reality of the magic is never questioned (and Scully’s a lot hotter than Abe).

While I can’t think of many reasons to tell you stay away from The Soul of Venice, I can think of less to tell you spend your money on it. The art’s pretty good, my personal favorite was the aforementioned “Night Train”, though I may be prejudiced since it had the strongest superhero feel and thus was more familiar (it even features a duo of superheroes: the WWII Lobster Johnson and his kid partner). Michael Oeming and Adam Pollina make particularly strong showings in the title story and “There’s Something Under My Bed” respectively (though Pollina’s art can get a little confusing during action sequences). Unfortunately, the strength of the art doesn’t carry the ho-hum scripts.

Part of the problem is that in spite of exactly what’s promising about the idea of multiple writers handling the same characters, for whatever reason, most of the writers in The Soul of Venice seem to be doing their best to ape Mike Mignola (Hellboy and B.P.R.D. creator). They just all ape him in their own unique ways.

And in the cases of the stories that try to go beyond Mignola’s style, like Brian Augustyn’s “Dark Waters” and Joe Harris’s “There’s Something Under My Bed”, they aren’t very good regardless. “Dark Waters” deals with the aftermath of the discovery of a trio of executed “witches," and the confusing dark powers a zealous preacher receives after viewing the bodies (I’ve read the story twice and still don’t completely understand how he got the powers in the first place). It's pretty preachy, which wouldn;t be a problem if the subject matter were a bit more topical. I think at this point most people accept the controversial “killing people you think are witches is BAD” message and we don’t need many more reminders. “There’s Something Under My Bed”, about a group of monsters who kidnap children from - yep, you guessed it - under their beds, looks and reads too much like Monsters, Inc. to feel like anything but an impersonation.

If you decide to give it a whirl anyway, do yourself a favor and either dig it up in your local library like I did or borrow it from a buddy. Knowing much less than I should about the economics of the comic industry, I usually don’t make much of a fuss about prices. But at $17.95 for 128 pages B.P.R.D.: The Soul of Venice & Other Stories seems way overpriced. You can get yourself trade collections that have more material and better material for a lot less than that.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)