Lone Wolf & Cub Vol. 2: The Gateless Barrier

Lone Wolf & Cub Vol. 2: The Gateless BarrierBy Kazuo Koike and Goseki Kojima

Published by Dark Horse; $9.95 US

304 pages

While Lone Wolf & Cub's first volume captured my interest, it was this second volume that convinced me I'd found a series worthy of my committed attention. Lone Wolf & Cub Vol. 2: The Gateless Barrier finds disgraced ronin Ogami Itto infiltrating a prison to solve the mystery behind an arson in "Red Cat," disguising himself as a military adviser to assassinate a traitor to the Shogunate in "The Coming of the Cold," learning the secret to kill the Buddha himself in the title story "The Gateless Barrier," and avenging the honor of a dead prostitute in "Winter Flower." The Gateless Barrier also brings us the first of many memorable and usually heartbreaking Daigoro solo adventures (or mostly solo) when the Cub half of Lone Wolf & Cub is used as bait to lure out his father in "Tragic O-Sue."

The most immediately noticeable difference between Lone Wolf & Cub's first and second volume is time, and in more than one way. First, most obviously, Koike and Kojima have more time per story and they use it well. While The Assassin's Road contains 9 stories - most of which are around 30 pages long - The Gateless Barrier contains only five 60 page stories, and this becomes the standard. Second, Koike is more willing to play with the sequence of events, choosing more often than not to start in the middle of the story rather than the beginning. "Red Cat," for example, opens with Itto carted off to prison. It isn't until after Itto kills a handful of prisoners and is sentenced to death that we are shown the beginning of the story and learn that his imprisonment is a ruse.

It's also worth noting that "Red Cat" is something of a continuation of "Wings to the Bird, Fangs to the Beast," the penultimate story of The Assassin's Road. A prostitute Itto saves in the latter story recruits him for the assassination in "Red Cat." The other stories up to this point are completely self-contained. It isn't a huge deal, and to be honest it's not even remotely necessary to read "Wings to the Bird, Fangs to the Beast" before "Red Cat" - in fact, it wasn't until my second read-through of the series that I realized the woman who recruits Itto in "Red Cat" is the same woman from the previous story, probably because the two stories are separated by the flashback origin story "The Assassin's Road" - but it's worth mentioning because, along with the doubling of Lone Wolf & Cub's page count, it's indicative of how popular the series became between the original publication of the stories reprinted between the first and second volumes.

Itto and Daigoro's relationship seems much more complex in The Gateless Barrier. In the first volume, there are moments when the contrast between Itto's ruthlessness and Daigoro's innocence almost comes off as gimmicky. Daigoro appears oblivious to the things his father does. When Itto drowns and stabs a ronin in the first volume, for example, and Daigoro responds by simply reaching out playfully for his father and laughing, it seems that the toddler has no concept of what's going on. The murder he helped his father commit could be no more than a game in his mind.

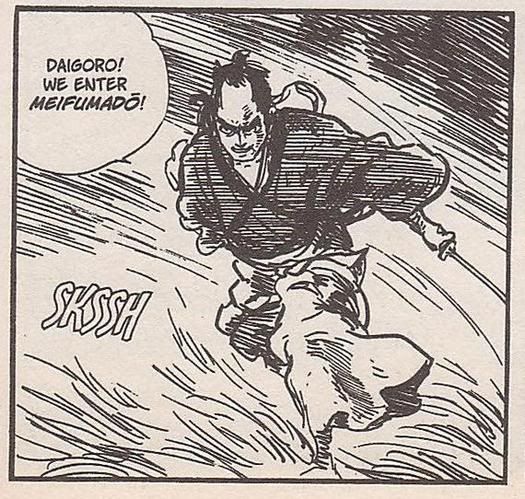

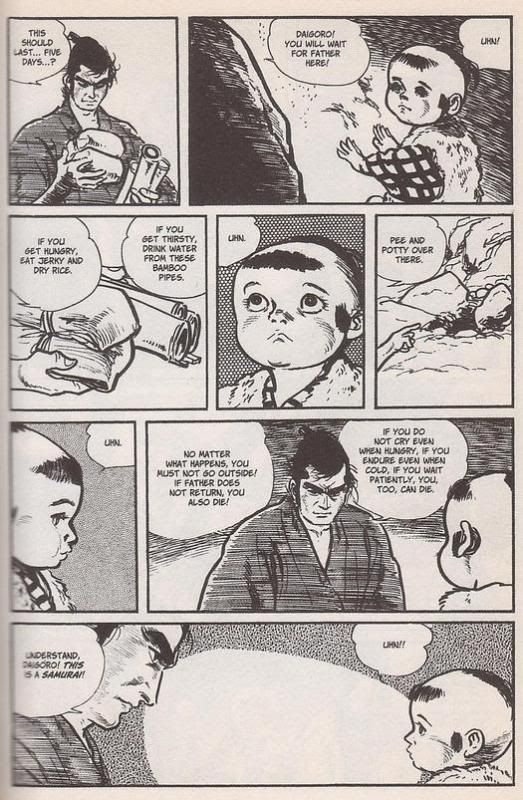

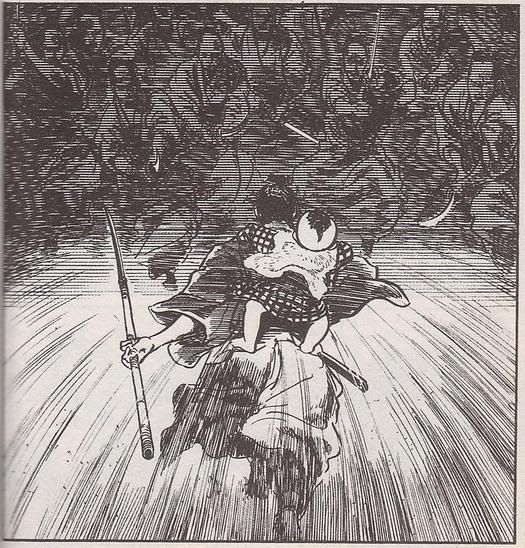

This changes in The Gateless Barrier. While Daigoro is clearly still a child in mind and body, Itto doesn't treat him as one. Itto expects Daigoro to follow a strict code and makes no allowances for Daigoro's failure, but at the same time Itto's love for his young son is clear to see. This is no more perfectly demonstrated than in the second story of The Gateless Barrier, "The Coming of the Cold." There is perhaps no scene in the series more perfect in displaying the strange, brutal, yet tender relationship between Lone Wolf and his Cub than one in which Itto instructs his son Daigoro how to survive in a cave while waiting for his father to complete his mission and how - if necessary - to die quietly and with honor. Daigoro responds with no emotion but clearly understands though he's still too young to do more than grunt cutely.

I often compare Ogami Itto to Malcolm Reynolds of Firefly and Serenity. While both Mal and Itto consider themselves to be less than they were - they in fact strive to be less than they were - neither can help but remain honorable and courageous warriors. You begin to learn this about Itto in The Gateless Barrier. He seems less of an assassin and more of a samurai. He still is an assassin. He still commits actions you could easily consider cowardly, murderous, and absolutely reprehensible; but his samurai roots shine through. In "Red Cat," for example, even after killing his target Itto goes further than he has to in order to solve a mystery and get vengeance for the fallen. A better example is "The Coming of the Cold," when Itto goes above and beyond for the sake of honor. For reasons I'd rather not spoil, Itto's clients willingly sacrifice both their lives and their names so Itto can achieve his goal. After killing his target Itto lectures his target's underlings to make them understand the reason behind the killing so his clients' names can be restored.

It was "The Coming of the Cold" that sealed the deal between me and Lone Wolf & Cub, and it remains one of my favorite stories of the series. It opens in the belly of a beached shipwreck - a perfect metaphor for Itto and Daigoro, two tattered survivors of a once grand and rich life - where Itto meets his latest client. Soon Itto travels to a land engulfed in blizzard. Daigoro must wait in a cave for his father and shortly after Itto leaves the cave, an avalanche covers the opening. Refusing to abandon his mission, Itto hopes for the best but accepts his son's likely death. After performing his mission, Itto manages to re-open the mouth of the cave and the story ends with Daigoro emerging from a blanket of furs, saying "Papa..." It's a heartbreaking moment and really the first time in the series that Daigoro's death seems a real possibility.

Another favorite of mine is the title story, "The Gateless Barrier," and it's a favorite for, I suspect, the same reason it was chosen for the volume's title. The specific message of "The Gateless Barrier" is one that is arguably the central message of Lone Wolf & Cub. Itto is hired to assassinate the Buddhist monk Wajo. Upon finding his target, Itto cannot make the fatal blow. He appears literally unable to physically strike the monk. Wajo explains Itto cannot kill him because he has attained Mu; that he has forgotten the self and become one with nothingness. Itto accepts this explanation and intends to kill himself in penance for his failure, but the monk urges him to find the gate where there is no gate and to become the Gateless Barrier. In other words, he has to go meditate a lot. Itto does, eventually returns to assassinate Wajo, and upon his death the monk says, "Is this not good? He who perfects his path? Is this not good? The gateless barrier?" The moral is one that is recurrent in the series; that it doesn't matter what path you choose as long as you choose a path and walk it well.

I've toyed with the idea of a top 10 list of favorite Lone Wolf & Cub stories and it's something I may eventually write. If so, Lone Wolf & Cub Vol. 2: The Gateless Barrier will likely make 2 or 3 appearances on the list. The learning curve between the first 2 volumes is Cliffs-of-Insanity steep, and the first volume is superb, so that's saying a lot.

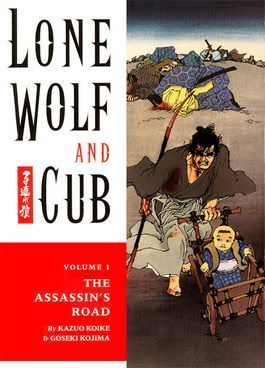

Lone Wolf & Cub Vol. 1: The Assassin's Road

Lone Wolf & Cub Vol. 1: The Assassin's Road