I’ve been working on this fucking thing since last November.

Actually, that’s not true. I first got the idea after reading

Alan Doane’s wonderful exploration of Frank Miller’s final issue of Daredevil, and if the date in the URL is right, that makes it July of 2004, meaning I’ve been working on this piece for the better part of a year. November was just when I sent ADD the e-mail to see if he’d want it.

Yeah, there are peripheral factors that could explain my procrastination: working and going to school full-time, helping my mother with her various medical issues, every now and then trying to squeeze in time to pay attention to the nice woman who’s kind enough to sleep with me, etc.

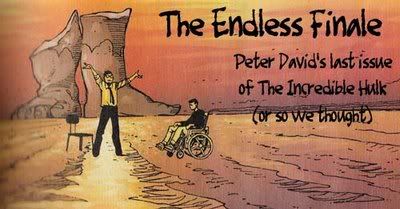

The real problem, I think, is that I’ve tried to be very professional. Detached. Unbiased. Every time I’ve started to write a review of

The Incredible Hulk #467, "The Lone and Level Sands" -- the last issue of Peter David’s original twelve-year run on the title -- I’ve tried to write it from the perspective of someone who isn’t a shamefully loyal Hulk-nut; who doesn’t see every empty space in his collection of David’s

Hulk as an unpardonable sin; who didn’t absolutely dread the idea of publishing online negative reviews of Peter David’s work and considered it a Herculean act of bravery when he finally did; who didn’t initially consider turning down his girlfriend’s offer to cohabit because he was afraid her cats might break his Randy Bowen Hulk statue; who didn’t leave his girlfriend alone to eat lunch in a pizza parlor because he was afraid he might not be thirty minutes early to the

Hulk film; whose forgiving girlfriend didn’t buy green drapes for their office (once he capitulated to cohabitation, after realizing the statue was much too heavy for the cats to topple) to match his Hulk posters. And mirrors. And clocks. And stickers. And action figures, model kits, coloring books, baby shoes, coffee mugs, twisty straws, Christmas ornaments, mini-busts, stamps, cards, bobble heads, key chains, sunglasses, board games, lunchboxes, wastebaskets, baseballs, cardboard stands, t-shirts, matchbox cars, electronic talking hands, and probably some other stuff (mostly green).

But I can’t, and considering the genius of "The Lone and Level Sands," it’s only the truly bugfuck-crazy Hulkophile who can see how masterful David’s finale was, and why.

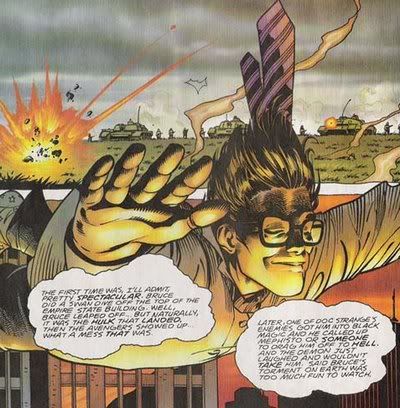

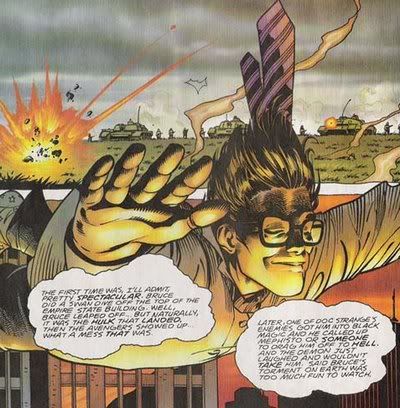

The entire story is told in flashback, with an aged, chain-smoking Rick Jones recounting the aftermath of Betty Banner’s death (she dies in the previous issue) on the tenth anniversary of her demise to a Daily Bugle reporter. Most of the story is told in double-page spreads with Jones’s hand -- a cigarette scissored in-between his index and middle fingers, the smoke curling up the sides of the pages and through the gutters–breaking only to return to Jones at the end as his eyes grow heavier, the ashtray gets more crowded, the fire grows smaller, and the various superhero paraphernalia (alluding to the vast trophy chamber seen in

Incredible Hulk: Future Imperfect) are swallowed by the shadows.

David and Adam Kubert create a beautiful montage of the aftermath of Betty’s death–from the more familiar scenes like old Thunderbolt Ross stupidly blasting at the Hulk with a handgun; to the tragic grace of a grinning Bruce Banner taking a swan dive off the Empire State Building.

Through Jones we learn of Bruce’s first suicide attempt, his subsequent imprisonment, his escape, a brief glimpse at the Hulk’s future battles and adventures (most of which, of course, have yet to come if ever, though Chris Cooper may or may not have been attempting to be faithful to the reference of a "face-to-face with Namor" with the

Hulk/Sub-Mariner 1998 Annual), Betty’s funeral and the gathering of superheroes it drew, and a final meeting between Jones and Bruce Banner. David throws in the fates of some of the series’ peripheral figures (e.g., the citizens of Freehold, the vengeful Armageddon, and the time-traveling Janis Jones) for good measure.

Something always nagged at me after re-reads of the story, and it didn’t take me too long to figure out what. As much as I’ve long considered it the perfect Hulk tale, there was something about it that simply made no sense. The title, "The Lone and Level Sands," is the thing.

The line comes from a Percy Shelley poem that Banner recites to Jones as his long time sidekick visits him in prison after his first suicide attempt. The poem speaks of Ozymandias, "King of Kings," and the traveler who finds his shattered statue in the desert. "I can see it, Rick," Bruce tells Jones. "The broken legs standing there...barefoot, the cuffs torn. The Hulk’s feet. And that broken face, lying half-buried in the desert...My life, a shattered ruin."

A powerful image, but does it fit? This is the Hulk we’re talking about. The poem is about a man who built a kingdom, but succumbed to the inevitable. How is the analogous to the Hulk? What has the Hulk built? And what has Banner built, besides the Hulk? What did either create that’s worth mourning its destruction?

The answer is that it isn’t strictly the Hulk who David is talking about. David blatantly injects himself into the story from the very first page–the unseen Daily Bugle reporter is named Peter (and for a nice little double entendre, we all know someone else who’s worked for that rag with the same first name).

Most often we hear David through Rick. David purportedly left the title over a creative dispute regarding the future of the Hulk, and Jones refers to Betty’s death as "the day the Hulk started down the road he never wanted to travel." Rick’s final monologue can easily be read as David’s farewell to his readers: "I could keep on telling stories about the Hulk...keep on going...but there’s other things in life, you know? It’s like what Bruce told me. Realize what’s important...family, loved ones...that’s the important thing." He includes a continuity loophole for subsequent writers who would doubtlessly steer clear of his version of the Hulk’s future: "So maybe I’m an alternate timeline. Who knows what’s really fated or ‘official?’" He ends fittingly with, "I’ve said enough."

David switches seats in the narration, from Rick to the reporter to the Hulk himself. We hear him lamenting his departure from the series when Banner laments the loss of Betty during a meeting with Rick in a military prison, but when he subsequently transforms into the Hulk, Rick tells us, "I’d seen so many things in his eyes over the years. Anger, resentment, betrayal, exhaustion...but in all those years...I’d never seen him look at me that way...with envy. And then he was gone." Considering we already know this is apparently the road the Hulk, "never wanted to travel," it seems likely the Hulk’s envy is leveled at David himself: the writer who will escape this unwanted path, while the Hulk will remain. During Rick’s last meeting with Banner, Bruce leaves him with, "Sometimes it’s best to move on," and in a nice symbolic gesture the scene opens with Bruce sitting in Rick’s wheelchair. Even the unseen reporter switches places. Despite his first name, he often resembles the reader more closely than the writer: "Look...I hate to keep you...but there’re so many other things I’d like to hear..."

But while David wrestles with his own demons throughout the story, it’s far from self-indulgent. Ultimately, the Ozymandias/Hulk analogy does fit, because of the one theme that consistently distinguished Peter David’s Hulk from those that came before and after.

Contrary to popular opinion, not all Hulk fans were happy with Peter David’s interpretation of their favorite muscleman, particularly in the case of the so-called "Merged" or (the name that Paul Jenkins’s misreading of David’s run helped him create) "Professor" Hulk: an incarnation that came about after Doc Samson brought Bruce Banner’s personality together with that of the childlike green Hulk and the thuggish gray one. A cunning, green strongman with the IQ of a rocket scientist is what emerged, though when you strip away the bigger words and not-quite-as-tattered clothes, on the surface the Merged Hulk was never really much different than his savage counterpart. You could often throw a "Hulk" or a "puny" into the Merged Hulk’s dialogue with predictable results, often changing a line like "Pathetic humans. Getting in my way," (

Incredible Hulk #383) to "Puny humans! Always getting in Hulk’s way!"

Ambition is what distinguished David’s Hulk from the previous interpretations, which probably has more to do with some fans’ dislike of Peter David’s tenure on the title than anything else. He didn’t have to count on money he’d stitched into his pants which would somehow survive a fall from orbit after battling the Toad Men. He didn’t have to sleep in the woods or in the houses of trusting strangers. The Hulk had been the world’s most powerful hobo, even stealing food from the campfires of homeless men and family reunion picnics in some stories. By gathering some semblance of control over his life, Bruce Banner and his alter-ego became less pure in some eyes, and perhaps less of a hero. Ambition is what made the Maestro of

Future Imperfect -- an evil, future version of the Hulk who ruled over the last vestige of humanity on a post-apocalyptic Earth . It’s why the Hulk’s membership into, and eventual leadership of, the Pantheon -- a paramilitary group of that intervened in international crises without official sanction, whose founder was eventually revealed to be much less altruistic than he originally claimed -- was so important to the Hulk’s development. It was the first time since that fateful day in New Mexico that either Banner or the Hulk had wielded any kind of power or control, except the kind that came from an emerald fist.

Part of what makes this story the perfect ending not only to Peter David’s initial run on

Incredible Hulk, but to the story of the Hulk as a whole, is that it’s less than an ending, and at the same time it’s so much more.

It’s the ongoing aspect of superhero comics that both renders the characters immortal and makes them less than characters. Stories end. Superheroes do not. They’re like endless porn scenes. The money shot’s never gonna come. If Luke Skywalker were a superhero, Vader’s emphysema would still fill theater speakers every few years. If Frodo were a superhero, he’d still be stumbling towards Mount Doom. If William Wallace were a superhero, he’d be wrestling the Brits for centuries to come (and it would probably be a CrossGen book). Stories end. Characters die. A story that never ends is not a story. A character that never dies is not a character: it’s a franchise.

Peter David achieved the impossible with

Incredible Hulk #467, by circumventing the necrophilia of the superhero genre. Before bowing out of the green-sometimes-gray goliath’s franchise, he wrote the endless finale to a story that can’t ever end. And while, upon reading it, you will know that it’s a story that only Peter David could write, it’s a story you’ve known for a long time. You’ve felt it in your bones. David wrote it, but you knew it before you read it. David wrote it, but so did Lee and Thomas and Wein and Stern and Mantlo. Despite the fact that the Hulk series continues, despite the various limited series and guest appearances, despite even David’s own

Incredible Hulk: The End, "The Lone and Level Sands" is the last Hulk story. It’s the only Hulk story. And it’s certainly the best.

FIGHTING YANK #1

FIGHTING YANK #1

Ever watch Family Ties? Remember when they’d call Tom Hanks in to play the alcoholic Uncle Ned? He showed up twice if I remember correctly, and once gave Michael J. Fox a nice crack upside the head (something most male watchers of the show envied Hanks for, I’m sure). At the time, I was just a little Hulkling, and to me those shows were the height of serious drama. That and, of course, that Different Strokes show when the old guy touched Gary Coleman and his goofy buddy in inappropriate ways.

Ever watch Family Ties? Remember when they’d call Tom Hanks in to play the alcoholic Uncle Ned? He showed up twice if I remember correctly, and once gave Michael J. Fox a nice crack upside the head (something most male watchers of the show envied Hanks for, I’m sure). At the time, I was just a little Hulkling, and to me those shows were the height of serious drama. That and, of course, that Different Strokes show when the old guy touched Gary Coleman and his goofy buddy in inappropriate ways.  SUPERMAN: RED SON

SUPERMAN: RED SON

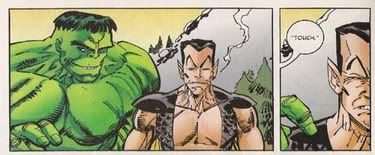

There are a lot of reasons why The Defenders failed to draw in enough readers to stay afloat. The heads of the project––Kurt Busiek and Erik Larsen––were both suffering chronic health problems while working on the series. Many readers took the plot device of Yandroth’s curse––a curse cast upon Hulk, Dr. Strange, Namor, and Silver Surfer, the so-called “Big Four” of the team––as a cheap and easy gimmick to explain how the four loners could bear to work together. In comparison to Avengers and JLA, only one character in the team––the Hulk––had his own ongoing monthly, and Larsen’s involvement in the title injured any hope that the green goliath’s presence would boost sales (many Hulk readers liken Larsen to the Anti-Christ, due in no small part to the fact that the green goliath has managed to get the crap beaten out of him in just about every Hulk-related story Larsen wrote previous to Defenders, as well as the nasty spats––most notably in the letters pages of Savage Dragon––Larsen has carried on with Hulk sacred cow Peter David). The Rogue’s Gallery of the Busiek/Larsen run read like the Punisher's “Don't Waste Ammo on The Following” list. And, of course, there were precious few X’s appearing anywhere in the mag.

There are a lot of reasons why The Defenders failed to draw in enough readers to stay afloat. The heads of the project––Kurt Busiek and Erik Larsen––were both suffering chronic health problems while working on the series. Many readers took the plot device of Yandroth’s curse––a curse cast upon Hulk, Dr. Strange, Namor, and Silver Surfer, the so-called “Big Four” of the team––as a cheap and easy gimmick to explain how the four loners could bear to work together. In comparison to Avengers and JLA, only one character in the team––the Hulk––had his own ongoing monthly, and Larsen’s involvement in the title injured any hope that the green goliath’s presence would boost sales (many Hulk readers liken Larsen to the Anti-Christ, due in no small part to the fact that the green goliath has managed to get the crap beaten out of him in just about every Hulk-related story Larsen wrote previous to Defenders, as well as the nasty spats––most notably in the letters pages of Savage Dragon––Larsen has carried on with Hulk sacred cow Peter David). The Rogue’s Gallery of the Busiek/Larsen run read like the Punisher's “Don't Waste Ammo on The Following” list. And, of course, there were precious few X’s appearing anywhere in the mag. Larsen’s penciling rarely seemed to be of the same caliber seen in Savage Dragon or The Amazing Spider-Man. Even some of the covers seemed like they were thrown together at the last minute, and on the few occasions Ron Frenz filled in for Larsen, the contrast in quality was so staggering you couldn’t help but feel sorry for the regular guy.

Larsen’s penciling rarely seemed to be of the same caliber seen in Savage Dragon or The Amazing Spider-Man. Even some of the covers seemed like they were thrown together at the last minute, and on the few occasions Ron Frenz filled in for Larsen, the contrast in quality was so staggering you couldn’t help but feel sorry for the regular guy.

The Defenders was funny. At times–like The Defenders #6, an issue narrated by the Hulk and which, should I ever decide to compile a Top Ten list of favorite Hulk stories, has a damn good chance of finding a home there–it was absolute chair-rocking hilarity. In fact, the few times I had complaints about the title, a lack of successful humor was usually to blame.

The Defenders was funny. At times–like The Defenders #6, an issue narrated by the Hulk and which, should I ever decide to compile a Top Ten list of favorite Hulk stories, has a damn good chance of finding a home there–it was absolute chair-rocking hilarity. In fact, the few times I had complaints about the title, a lack of successful humor was usually to blame.

AVENGERS FOREVER

AVENGERS FOREVER AQUAMAN: TIME AND TIDE

AQUAMAN: TIME AND TIDE